General Use

Grades of DE and their uses

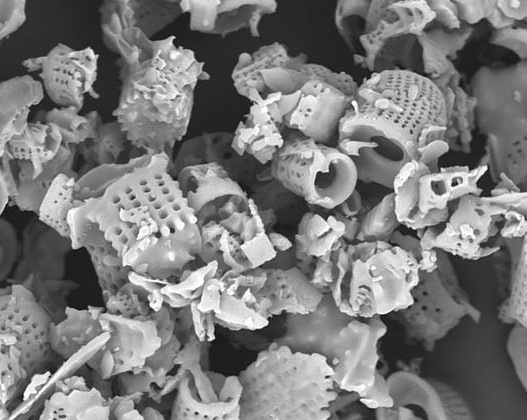

Diatomite is comprised mostly of the skeletal fossils of diatoms and classified as a siliceous sedimentary rock. Diatoms are aquatic algae related single celled organisms which are porous in structure. For this reason diatomites are most commonly used as a filtration material.

It is not chemically reactive and looks much like chalk while dry; however, it is a great deal lighter. The purposes of diatomaceous earth date at least as far back as 15 CE in Greece when it was used in brick making and pottery.

Deposits of diatomite have been found all over the world; however, those that are pure and viable for marketing uses are the exception to the rule. The uses of this inert substance are extremely wide ranging which include the processing of thousands of products and the actual production hundreds. Some of the characteristics of diatomite which render it marketable are listed below.

-

DE has insulating qualities.

-

It offers abrasive attributes.

-

DE is extremely porous.

-

It has a high silica content.

-

DE possesses a high capacity for absorption.

-

It offers a large degree of surface area.

-

The density level of DE is low.

-

DE is chemically unreactive.

Amorphous Silica vs Crystalline Silica

Diatomaceous earth may first be divided into non-calcined and calcined. The differences in these are the essential variable which determines the purpose of each. DE that has been heat treated with temperatures in excess of 800 ºC. This process is necessary to produce a more effective filtration agent. The heat is a catalyst which transforms amorphous silica into crystalline silica.

This form should not be used for any type of consumption as the crystalline silica can cause toxicity in humans and animals. It should not be used for food storage purposes or inhaled. This form is often referred to as pool grade DE.

The non-calcined form of diatomaceous earth is natural and is not treated with heat of intense temperatures or chemicals. Amorphous silica is not considered to be hazardous to the health of humans or animals. In order to be labelled as food grade the crystalline silica content must be under 1%. Those which are calcined may carry a crystalline silica content as high as 70%.

Freshwater vs Saltwater

One of the most significant uses of superior quality diatomite is as a filtration media for the production of wine and beer as well as the manufacturing of pharmaceuticals. The structure of the fossils resembles that of a microscopic honeycomb lends the effective filtration properties. Pool grade diatomaceous earth in mined from ancient saltwater beds while the food grade version is derived from dry primordial freshwater beds.

DE: Industrial Uses

-

Today DE is used in manufacturing personal hygiene products such as toothpaste, facial cleansers, exfoliators, and numerous powder based cosmetics.

-

It is used to create filters for pools and aquariums as well as wineries and breweries.

-

Diatomaceous earth is used in processing motor oil and the manufacture of pharmaceuticals.

-

It is used to alter the sheen and gloss of paint as well as increases strength and bulk. DE also enhances the adhesion of coatings and regulates permeability.

-

Diatomaceous earth is used in the production of plastics as an anti-blocking agent. For instance this is what makes plastic bags slide easily from the package instead of sticking together.

-

It is used to absorb spills in several types of industrial setting such as waste treatment facilities, automobile manufacturers, and janitorial services.

-

Diatomaceous earth is add to soil to increase the permeation of air and water as well as decrease compaction. It serves as an amendment to loosen compacted soil, increase drainage, and promote root growth.

-

Areas with a high level of controlled landscape such as golf courses employ DE to absorb and retain water thereby decreasing the quantity of water required.

-

It is extremely abrasive and can puncture the waxy exoskeletons of insects and its absorption capacity drains them causing death by dehydration. It is not possible for pests to build an immunity to its effects. As an insecticide diatomaceous earth is effective in both residential and commercial settings.

-

Diatomaceous earth is used in agricultural settings as an insecticide for gardens and structural treatments of grain storage.

There are many other uses of DE that most never realize such as to coat seeds, create paper, make specific types of concrete, and for dental fillings. The oil industry uses it as a thickener compound for drilling. Diatomaceous earth has also found a place in the production of sealants, roofing compounds, and adhesives.

Grades of DE explained

While DE has been around and used for perhaps thousands of years it has only recently reach popularity on the consumer market. Individuals all over the world purchase diatomaceous earth to use for many purposes in the home, yard, barn, and yard. It has become widely available both in brick and mortar shops as well as online.

-

Diatomaceous earth is an effective method to rid homes of annoying pests such as cockroaches, fleas, beetles, and bedbugs. It is excellent for use in the garden and barn as well.

-

DE is a great odour eliminator to use in litter boxes, refrigerators, and carpets.

-

Many pet parents use it to eradicate fleas and ticks from pets.

-

For those who keep a well-stocked pantry can use it to store dry goods and protect them from weevils.

-

Diatomaceous earth works well as a soil amendment and insecticide in home gardens.

-

It soaks up spills in garages and home workshops.

-

DE is an effective as a household cleaner due to its abrasiveness. It may be used as a metal polish or to scrub tough stains.

Note: Only food grade diatomaceous earth is natural as it is not heat or chemically treated. It alone should be used for purposes in which there is risk of direct exposure. Pool grade DE is not only ineffective for destroying insects, it can also be a health hazard. It is important to purchase food grade diatomaceous earth from reputable sources.

While Diatomaceous Earth, often abbreviated as DE, is marketed for a wide variety of uses, there are two standard grades of this substance. Food and industrial grades are further divided into branched categories by more specific uses. Diatomaceous Earth consists of microscopic diatoms fossils which are minute aquatic organisms. The skeletons of these tiny little creatures are made of silica, a naturally occurring substance in the crust of the earth.

Diatomaceous Earth was first marketed as a pesticide in 1960. It is effective against many types of pests; however, this substance is not innately poisonous. The fossils which make up DE acts as drying agents and are extremely abrasive. As insects move around within it, sharp edges of the fossils cut their bodies and the silica wicks moisture from them. DE is divided into grades for specific purposes. DE currently has more than 150 registered private and commercial purposes. Industrial grade Diatomaceous Earth has been calcined by treating it with heat. In this form it is not safe for consumption and often contains high levels of crystalline silica which can cause silicosis.

Food grade Diatomaceous Earth has a wide array of uses for outside and inside. Examples are in gardens, on farms, inside buildings, and animal kennels. Food grade DE is made up of natural amorphous silica which is the freshwater form. It consists of less than 2% crystalline silica. This form of DE also contains beneficial minerals such as calcium, zinc, and magnesium; however, it has either a minute amount or no toxic metals such as lead, Cadmium, Arsenic.

-

One of DE’s most common uses is to prevent animal feed from caking.

-

Added to grain Diatomaceous Earth can protect it from insects such as weevils and grain moths.

-

It can safely be used to help rid animals of common pests such as fleas and ticks.

-

Diatomaceous Earth is used for protection against spiders and bed bugs as well as to prevent infestations of crickets and cockroaches.

It is very important to only use the recommended grade of Diatomaceous Earth for any purpose. Industrial grade can be harmful to humans and animals; however, food grade is created to be safer. While it is a natural occurring substance, any grade may be hazardous, if it is used for purposes other than that which it was designed for.

Improves Bone Health

The silica which DE is made of improves bone mineral density and joint formation. It is also beneficial to bone and connective tissue, preventing osteoporosis [1].

Natural Insecticide

DE helps to control bed bugs, cockroaches, ants, fleas and parasites naturally but drying the waxy exoskeletons of the pest, dehydrating and killing them [2].

Purifies Water

Diatomaceous Earth filters microparticles in water and is commonly used in water filters and purifiers. It can remove up to 80% of heavy metals and viral strains from tap water [3]. It is often used when manufacturing alcohol, sugar, and honey, as well as for purifying fish tanks.

Body Detox

In the same way that DE purifies water, DE also removes heavy metals from the body and neutralises free radicals and other toxins. As well as this, DE helps to eradicate intestinal parasites and viruses, cleanses the gastrointestinal tract and reduces gas [4].

Strengthens Hair, Skin, Teeth, and Nails

DE can assist in the metabolism of collagen and calcium for the formation of strong hair, nails and teeth. As well as this, its natural abrasive qualities polish teeth and skin, removing harmful toxins [5].

References

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2658806/

[2] https://aem.asm.org/content/57/9/2502

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10731501

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3546016/

Why Do Parrots (And People) Eat Clay?

This article was posted by npr.org and I have reposted it here as it is very interesting research that shows why we like to eat dirt!

you can view the original article here

The parrots of Southeastern Peru crave an earthy delicacy: dirt. At the Colorado clay lick, a cliff face rising above the Tambopata River in the western Amazon Basin, parrots — often hundreds at a time from up to 18 species — gather each day to feast on sun-hardened clay.

"It's a real spectacle of both sight and sound," says biologist Donald Brightsmith of Texas A&M University.

As director of the Tambopata Macaw Project, Brightsmith has spent 16 years leading researchers and volunteers who record the comings and goings of these hungry parrots. Their goal, in part, is to get to the bottom of what drives this earth-eating habit, which occurs throughout the region.

In a recent paper in the journal Ibis, Brightsmith and colleagues report results from over 20,000 hours of parrot observations stretched over 13 years. The findings suggest that clay may give parrots the nutritional boost they need to rear their young.

There are two main hypotheses for why Peruvian parrots practice geophagy — the intentional consumption of soil. The first is that clay is a natural detox treatment. When food is limited and safer plants are in short supply, clay could help birds eat the more toxic plants that remain. Indeed, some laboratory experiments have shown that clay could bind to toxins, keeping them out of a parrot's bloodstream.

The other hypothesis is that clay contributes vital minerals that a parrot's plant-based diet lacks. Brightsmith previously showed, for example, that parrot geophagy is concentrated in moist tropical forests where sodium — critical for nerve function and muscle contraction — is quickly washed from the ecosystem, except where it's stored in hard clay. Amazonian clay lick soils typically contain levels of sodium 40 times greater than the parrots' plant foods.

To test both hypotheses, the team studied how the clay-eating observation data matched up with other long-term data sets on food availability and breeding times. The team found no evidence to support the toxin-protection hypothesis — parrots actually ate clay more often when food was plentiful.

But their analysis did support the idea that clay works as a nutrient supplement for the birds. For every one of the nine parrot species studied, clay eating peaked during the breeding season, and was especially prominent as parents fed new hatchlings. "It's a time of nutritional stress, especially for the females," says co-author Elizabeth Hobson, a behavioral ecologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Santa Fe Institute. The mothers need more energy to produce eggs and enough nutrients to feed both their chicks and themselves. "Sodium is one thing that is very obviously missing from their diet, so in a time of stress, they may need more of that."

Brightsmith isn't surprised by these results. "Parrots eat toxic foods all over the world, but they only eat clay soils in select areas," he says. "All of the evidence keeps lining up that what is driving this is sodium, not toxins."

Many other animals, including elephants, bats and primates, also eat dirt. Field biologist Mrinalini Watsa, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, says that in all of these cases, scientists are testing the same basic detox-versus-nutrients hypotheses. "The data set that this paper used is absolutely incredible to be able to answer that," says Watsa. "Nothing like that exists for the primates that I study."

Watsa is exploring why saki monkeys eat soils from termite mounds. She works in the same region of Peru as the parrot researchers, but she's already ruled out the sodium explanation for her species because she didn't find high levels of the mineral in the mounds.

Nutritional anthropologist Sera Young of Northwestern University studies geophagy in another species: humans, particularly the pregnant sort. In her book Craving Earth: Understanding Pica—the Urge to Eat Clay, Starch, Ice, and Chalk, Young cites reports of pregnant women eating earth across the globe — from Tanzania and Iran to Mexico and the United States.

"Pregnant women are the hallmark of geophagy," she says. There are real risks associated with the practice. Some soil is laden with contaminants like lead. And eating too much soil can replace other vital foods in a diet. So why would pregnant women do it? No one knows for sure. While some researchers attribute the practice to culture, others suggest similar hypotheses to the ones scientists are testing in animals.

"The salt explanation doesn't hold water for explaining human geophagy," says Young, since human diets are typically not salt deprived. Pregnant women and parrot mothers may not crave clay for the same reasons. And even with the parrots, Young would like to see the researchers follow up their study with a more direct test using controlled lab experiments.

Hobson agrees that her team's results, as with all correlational studies, should be taken with "a grain of salt." They didn't test, for example, how the birds react when given chunks of clay that differ only in sodium content. Brightsmith says they are working toward setting up controlled studies using captive birds in the future.

Of course, one advantage Young has over the animal researchers is that she can ask her study subjects directly why they eat clay: "They talk about the texture and the smell," she says. "Then they say, 'I like the taste. But what compels me is the smell of damp earth. My mouth just wants it.'"

Carolyn Beans is a freelance science journalist living in Washington, D.C. She specializes in ecology, evolution, and health.

.png)